Travel Dish spotlights Michelin-star and James Beard Award-winning chefs, master mixologists and global gourmet treats that you can recreate at home.

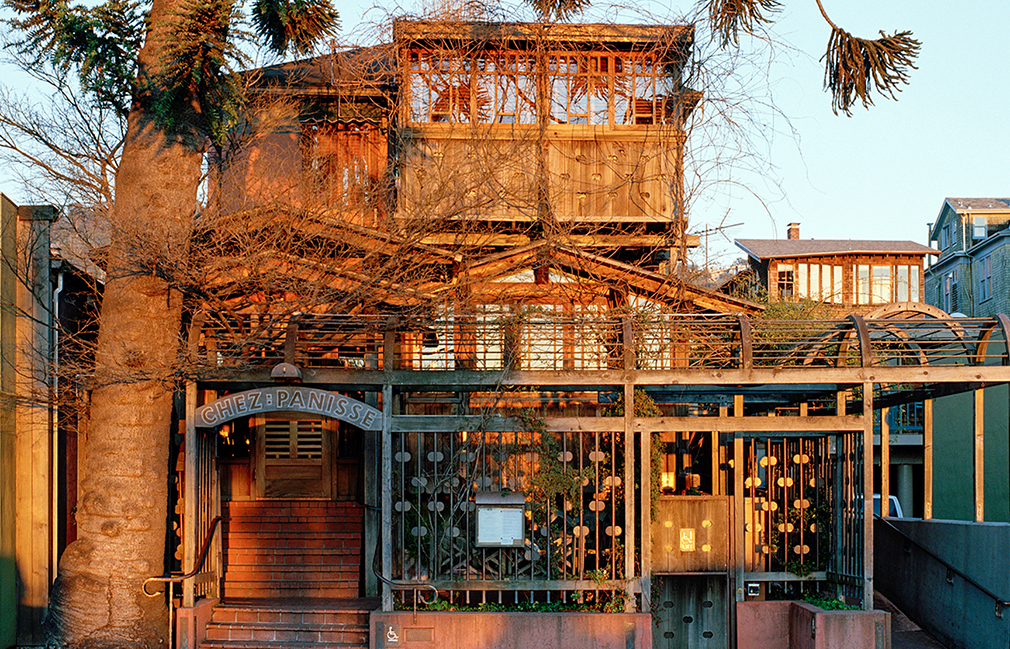

After half a century in Berkeley, chef, author and food activist Alice Waters decided to partner with the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles to open Lulu – the first restaurant outside of her groundbreaking Chez Panisse in the Bay Area where she brought diners farm-to-table California cuisine.

At the L.A. restaurant, longtime Chez Panisse chef and author, Chef David Tanis is at the helm while incorporating the same regenerative ‘market cooking’ philosophies with a few new surprises.

We caught up with the legendary ‘restauratrice’ just as she was preparing for the first mock in-door lunch service at Chez Panisse since the pandemic restrictions, to find out more about her charitable pursuits, favorite garden project, why she wanted to open in Los Angeles (where her daughter lives) and what surprise menu item she insisted on.

After 50 years, why did you feel this was the right time to expand outside of Berkeley to Los Angeles?

I never thought about it that way. I was called by the director of the Hammer Museum Annie Philbin to see if she knew anybody who could run the restaurant there. I thought it would be great to do it and connect the dots between art and food. What was more important for me, was to be part of the University of California because I have been working with them for the last two years and I know they have a carbon neutrality initiative for 2025. Because food could be part of that, I spoke to Janet Napolitano and the new University of California president Michel V. Drake about it. I think they are really going to change their procurement to local, regenerative and organic. And, I just knew that it would a beautiful place [for a restaurant] in the courtyard at the Hammer to gather with people and connect with UCLA and help to make this happen.

What are some of your favorite dishes that Chef David Tanis creates at Lulu?

The three-course menu at lunchtime. Chef David Tanis is able to fold in the food of many cuisines from around the world and make them feel harmoniously seasonal and Mediterranean in spirit and I love that about his cooking and the beauty of his dishes like the bouillabaisse.

His salads are special but I insisted on the hand-made potato chips! We wanted a predictable bar menu and place where you could get a sandwich, potato chips and have certain things when they came during museum hours whether for a cup of coffee and a mullet muffin or a glass of wine in the late afternoon.

It is exactly what I wanted but it’s changing in terms of season. That for me is the most important part, that it really reflects that moment in time and when it’s over, it’s over. That’s what has kept Chez Panisse alive. Everybody can count on the food being nutritious and organic. They can depend on that and that is really where I want to connect the dots.

How would you describe your role as a restauratrice? Does this mean you are spending less time in the kitchen and more time and causes and your charitable foundation work?

I love that word. It’s a French word for a woman who runs a restaurant. I see myself as a collaborator and a taster. I’m have not been cooking at the restaurant but I’ve been receiving the food to go from the restaurant. I’m tasting it, calling the chef up and talking about it and giving my feedback. They count on me and I count on them. That is the role that I always loved. I have really not been in the kitchen in many years.

But you are still very much involved in the day-to-day Chez Panisse?

I’m always looking at the menus and I know what is going on all the time. We are reopening the restaurant again next week and fine-tuning the menu. I’m so pleased with it. I feel like that is absolutely my role, I’m connecting and communicating in a collaborative way. I call it a little bit regenerative way of cooking. Everybody tastes in the kitchen when we do a meal. All the cooks and waiters can taste and give an opinion. It’s the chef who evaluates that but everybody has a voice. It’s always been that way. When we do that, we all create something greater than the sum of the parts and I can’t imagine having a restaurant where that conversation it’s happening. It’s the best way to put a meal together and it has always worked in a beautiful way.

Now that children are going back to in-person classes, do you have any new initiatives planned for the Edible School Yard Project?

This is the main foundation that I’m involved in. It started at a middle-school in Berkley with 1,000 students speaking 22 different languages. We made a garden classroom and kitchen classroom but not to teach those things per se but to teach the academic functions like math, science, language, art, music. Maybe they are making tortilla soup and learning Spanish. It’s a very Montessori way of learning by doing.

What gives me the real foundation to believe that we can teach the values, is this project is 26 years old and people come from around the world. We have a network with over 6,000 schools and in every state of the U.S. I know they believe in the stewardship of the land and organic food, and they understand about nourishment and community building. This is all part of the ESY network. I’m convinced the idea of edible education can be at any school, any climate, any age group in the world and students really benefit from being in nature and learning how to cook and eat together this is very important for our society.

As an advocate of Slow Food and Farm to Table, do you feel that American’s are making better choices when it comes to eating for our health?

I really wish I could say yes!

I wrote a manifesto called ‘we are what we eat.’ It’s theories that I have: If you eat fast-food you eat the values that come with the food and they become part of your life. Time is money. Everything should be fast, cheap and easy and uniform – and it doesn’t matter where it came from. These ideas have changed our world.

I grew up in New Jersey and we never ate anything that was out of season and we never imported food, except for coffee, tea and spices. It was a different world and we will never be able to eat the right food unless it’s local. I want to know where my food comes from and how did they farm it. I do think there is a healthy, strong movement of farmers markets around this country and people are caring about how bread is made. That is so important and it has thrived during the pandemic. But the fast-food industry is about deception. Eating healthy is not just fruit and vegetables. It’s where they came from and how they are grown. I don’t think they are healthy if they are grown with pesticides. Health begins in the soil. I’m a slow food person and I really want to win people over with taste. That’s what has what happened at the Edible School Yard. It’s taste and to be outside and connecting with the beauty of nature and to fine-tune what you have in your bowl to your own taste. And, it’s very exciting to observe the enthusiasm of all those kids.

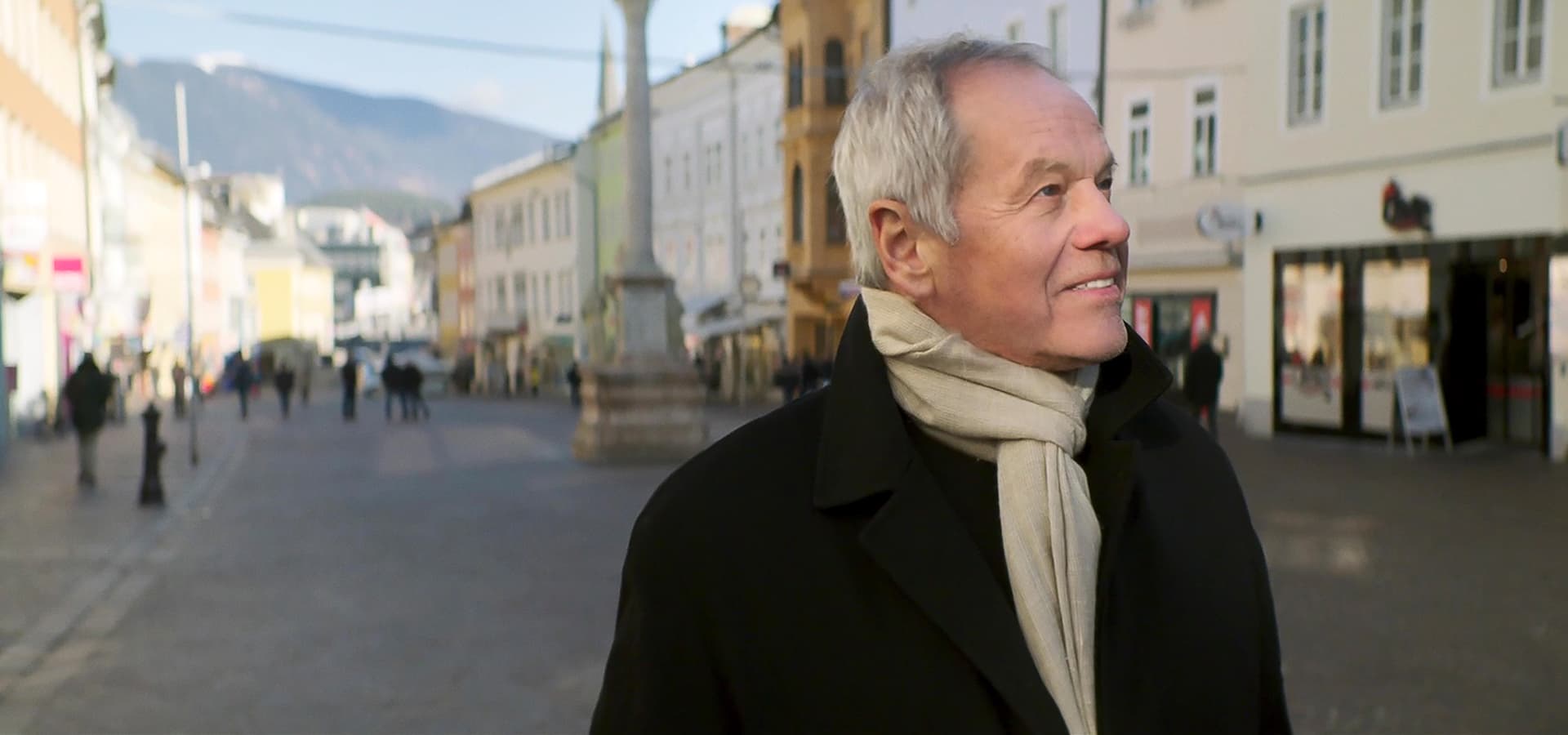

Another person trying to make changes in the food industry is Chef Roy Choi. Can you tell us what was the most interesting part of appearing on his PBS series Broken Bread and why you wanted to be part of the program?

I love his curiosity and warmth. They are very few people you meet them and you feel deeply connected. He is one of those people. He is so non-judgmental and looking for what you’re interested in and creating a convivial table. He’s a very unique person and I think everybody who meets him has that sense. And, it was so special to see Wolfgang [Puck] on his show. I have not talked to him in years and [Roy] was able to bring us together in a beautiful way. Wolfgang spoke about taking his child to the farmer’s market – he knew how to make us feel close. I was very impressed and comfortable and I’m usually not in television circumstances.

Where are some of the places around the world, or closer to home, that you are looking forward to exploring this year?

At the end of March, I’m going to New York and Washington DC for a big climate conference and art exhibit at The Kennedy Center. I’m on the panel with a group of many government people. I hope we have an opportunity to talk about school-supported agriculture. I think this is the only positive way we can address climate, health and the values of our democracy in the world. I’m still in the place of believing that the way to change the world is to teach these values to children at the public-school systems globally. I know that’s ambitious but I see food as universal education.

Then I’m going to Italy for Slow Food and the American Academy in Rome where I’ve been working on a project for 15 years. It’s such an amazing institution and they have one farmer there that they buy everything from and he’s amazing. They are doing simple, beautiful food. I’m going to help select a new chef. Then I’m going to Greece for a friend’s wedding. I have not been since college and I’ve always wanted to go back. I’m looking forward to it because I love the simplicity of the food and I know it will lift my spirits.

If you could spend time working in anyone’s garden, other than your own, where would that take you? And what would you plant?

I love The White House Garden. I was very excited about working with Michelle Obama on that, right after President Obama took office. And [the pictures] of that ‘victory garden’ went around the world.

It’s so important that the White House again reflect these values and you could see what they support. It says something dramatic about our democracy, about the care of the land and climate. I want the current President to say ‘plant a ‘victory garden’ and make it organic and we will give these public lands to people who want to grow food.’

They have 25 different varieties of strawberries [at the White House], and that alone could really inspire someone. I ended up planting a lot of lettuce and cilantro, but also passion fruit and blueberry bushes. The animals ate my carrots but it’s trial and error. How do you know what the deer are going to eat? I’ve always had an herb and salad garden, it’s important to see what grows and understand the big picture about biodiversity.

French Lentil Salad with broccolini and soft-cooked eggs from Chef David Tanis at Lulu

- Cook 2 cups of French lentils in a small pot with salted water, a bay leaf and a thyme sprig.

- They should be done in about 30 minutes. Drain.

- Cook 1 cup of diced onion with ½ cup diced carrot and ½ cup diced carrot in a little olive oil until softened.

- Combine cooked vegetable mixture with cooked lentils. Season with salt, pepper, a little chopped thyme and parsley, and a splash of r ed wine vinegar. Stir well, taste and adjust seasoning, adding salt, olive oil, and vinegar as necessary. Keep at room temperature.

To serve, garnish with lightly cooked broccolini and quartered 7-minute eggs (yolks can be a little runny, or firmer if preferred).